Production

MANAGING EDITOR & ART DIRECTOR / ZACH PEARL

EDITOR / LINDSAY LeBLANC

SUBSCRIPTIONS & DEVELOPMENT / YOLI TERZIYSKA

MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS / SARA ENGLAND

In consultation with

CAOIMHE MORGAN-FEIR

FRANCISCO-FERNANDO GRANADOS

& KATHERINE DENNIS

Contributors

ANOUCHKA FREYBE

BRUCE EVES

JESSICA BALDANZA

PARTICIPANT NO. 4

PREFACE

Bruce Eves, Work #998: BIRTH TO (NEAR) DEATH AND BACK AGAIN—In Four Parts, process work

Anouchka Freybe, CASTING BACKWARDS: The Importance of Re-Representing Trauma, process work

On September 3rd, 2015 KAPSULA Magazine hosted its first-ever arts writing workshop. With cultural partners, Carbon Paper and Gallery 44 Centre for Contemporary Photography, KAPSULA aimed to extend and adapt the experimental leanings of our content into an interactive, educational format.

The prophetically titled WRITER'S ROULETTE invited emerging to mid-career writers to ruminate on the subject of "risk in contemporary art" as well as enact degrees of risk and vulnerability in both the writing and editing processes. Participants were asked to come prepared with a paragraph or writerly "zygote" which would evolve through the exercises of the workshop. The subject of risk aligned with KAPSULA's Summer 2015 call for submissions and echoed a palpable aire of uncertainty surrounding the future of the arts in Canada (as the nation headed into its longest federal election).

Facilitated by Toronto-based artist, writer and former editor of FUSE, Gina Badger, the workshop proved a lively and engaged two hours of critical conversation, free-association writing and targeted peer-review. An emphasis on process was of particular importance to KAPSULA when conceiving WRITER'S ROULETTE. And, Badger had no shortage of conceptual tricks to help participants consider the profuse (and slippery) dimensions of their texts.

Afterward, participants worked with KAPSULA editor, Lindsay LeBlanc, to hone the raw material they'd forged in the workshop. The results of this risky confluence are published below.

CONTENTS

THINK PIECE:

Can Abstract Art Ever Be Risky Again?

by Jessica Baldanza

CASTING BACKWARDS

The Importance of Re-Representing Trauma

by Anouchka Freybe

Work #950: BIRTH TO (NEAR) DEATH AND BACK AGAIN—In Four Parts

by Bruce Eves

THE WAITING GAME

THINK PIECE:

Can Abstract Art Ever Be Risky Again?

When I speak of abstraction here, an infinitely broad genre of art making, I speak of the nearly neo-expressionist abstraction that has re-emerged over the past few years in all mediums, but especially in paint. From Julia Dault’s 2014 mixed media exhibition Color Me Badd at The Power Plant, to Max Brand’s first-place ranking on Artnet’s “10 Exceptional Millennial Artists to Watch” list this year, abstraction has consumed the contemporary art world—and the art market. One has to wonder about the source of abstraction’s comeback. One possible answer is that this work responds to the ever-increasing mass proliferation of images in our everyday lives. In an age where realistic imagery is in abundance, where our conception of high-resolution changes with every minimized pixel, it is understandable that we draw back to the basic elements of image making: color, line, shape and texture. Yet, this seems far too shallow to justify the kind of overwhelming return to abstraction happening now.

We exist in a post post-modern, post-internet state of art making. The exact name or movement summarizing of where we currently sit is impossible to say, as we lack the aid of time and perspective to understand what the general trends are. Nevertheless, what we can be sure of is art has already had its self-reflexive moment. Long gone are the days in which abstract art was a radical statement in the ongoing discourse around what is and is not art—when Clement Greenberg’s sweeping formalism was the legitimate method for appraising art’s merits. As such, why the return to abstraction now, when the novelty and risk of non-representational work has long since dissolved?

The cynical side of my intuition says that the revival of abstraction answers to an ever-hungry art market, complacent to bid over work that appears to be avant-garde but is in actuality painfully regressive. Take the hotly endorsed contemporary artist Christian Rosa, whose abstract works composed of tight coils and long squiggles in pencil, oil stick and spray paint look as if they could have been made by Cy Twombly many decades before, or even Picasso or Miro before that. Rosa’s works, allegedly exploring gesture and space, are not “bad” works per se—but certainly not risky, as they fit neatly amongst previous artists who comprise the canon of Western art.

Compare these types of works to Richard Prince’s highly controversial Instagram series, which re-ignited the debate surrounding intellectual property and plagiarism (a hot and relevant topic in an age where virtually everything is accessible online), or Niki Johnson’s portrait of Pope Benedict XVI “Eggs Benedict,” composed entirely of coloured condoms. Granted, this is not an entirely original gesture, but one that remains controversial by highlighting important conversations about access to sexual education and safety without cultural stigma. These are, debatably, risky works.

Of course, not all art has to be “about” something; the one consistent quality art has maintained over the course of its history is that none of its many definitions have ever stuck. But when a trend such as neo-expressionist abstraction comes to the fore, amidst a common mourning for painting’s death, it is important to look critically at the why. Often there is some indicated subtext behind art’s trends, be it political, art-historical or otherwise, but in its abstraction lies the unnerving sense that these contextual topics do not need to be explained, or even evident to the viewer, always remaining strategically opaque. There is security in the ambiguity of abstraction; a work can claim to mean anything and everything, when really it means nothing.

Overall, a question as complex as this one requires a much more thorough investigation, and likely has no finite answer. Nevertheless, it is important to consider the possibility that abstract art can never be risky again in order to stop art from entering an age of impotent creations and artistic clichés created only for their marketability. Safety, familiarity, and homogeneity have never lead to innovation before, and may hinder the development of an art that adequately responds to the present, now.

CASTING BACKWARDS

The Importance of Re-Representing Trauma

I came to the art practice of Esther Shalev-Gerz through her first German public commission The Monument Against Fascism (1986-1993). The commission was given to the artist and her then-husband Jochen Gerz, and was part of a seminal period in German national self-reflection that resulted in countless attempts at building memorials. At the time, in the mid-1990s, I was aware of being sheltered from what was once fascist Germany while also being implicated in the shame and shock passed on to my generation--the first in my family to come to Canada. My immigrant family did not know how to reconcile with the public memory of those years, as children born during the war. Perhaps they were caught in what Saul Friedländer has referred to as “deep memory”: something that remains essentially inarticulable and unrepresentable (Friedländer 1992, 41).

Esther Shalev-Gerz is an Israeli/Lithuanian artist who has been living in Paris since 1984. Born in Vilnius, Lithuania, she moved with her family to Jerusalem in the late 1950s and developed a fascination with telling stories through photography, slideshows, books, and sculptures. She became a mother in 1970. Shalev-Gerz enrolled at the Belazel School of Art and Design, completed her BFA in 1979, then taught sculpture in Israel. After spending some time abroad she moved to Paris, and in the early 1990s went to Berlin on a DAAD scholarship. There her work's focus changed as a result of the connectivity she experienced between audience engagement, talking, and the activation of ideas. She started work with video format in 1996. Since 2003, she has been a professor at the Valand Art School, Goteborg University in Sweden. Her work continues to address subjective experiences of difficult topics. Her chosen narrators are both the activators and objects of contemplation.

The Shalev/Gerz’s interest in confronting the past staged a release from sheltered confusion. It felt like an activation of responsibility transformed into what was really relevant: voice and dialogue. If the observer effect holds true, where the act of observation impacts its subject matter, we can affect change through dialogue. The loss is permanent, but the understanding of loss changes through ongoing observation. The Monument has had a talismanic effect on many, predominantly because of the counter-monument qualities that it has at its core, along with the commission’s purpose to challenge the post-war generation to remain vigilant and vocal. My initial experience with The Monument was in my early 20’s; now, years later, I’ve been absorbed by Shalev-Gerz’s continuity as she loops through personal and public stories. Her sensitivities are needed here, in parallel North American populations where we’re cast in the frightening position of witnessing our nation’s internal cultural divides and structural violence.

The Monument in its conceptual staging required spectators to find their voice within the piece. Residents of Hamburg and visitors alike were invited to support a public statement against fascism by inscribing their names upon the column’s four paneled sides--a kind of three-dimensional manifesto. In a personal interview, Shalev-Gerz spoke about the process:

…It was the first time that both of us dealt with public participation. People reacted very strongly to it… and that really focused for me that I wanted to work with the public solely. For me, it was the voice, it was the most complicated one. It reveals why we cannot speak, what is hindering us.

The leaden-dressed twelve-meter-high column would be gradually buried once all of its reachable surfaces were saturated with marks. Unveiled on October 10th, 1986 (almost thirty years ago) it was lowered in eight stages into its negative form: a shaft-like receptacle submerged underground. On November 10, 1993, it was covered with a burial stone. While funereal in process, the lowering or disappearance of the column speaks to the nature of memory as a casting, the lived experience that informs its shape, and the “afterlife of memory” aggravated by the need to reengage and reassess. The Monument does not represent trauma as resolved. Rather, it establishes dialogue around loss as a shared responsibility: what Sisyphean process it is to be absorbed in the memories of trauma and loss. And we all carry this, as surely as that column continues to exist below the surface.

University of Massachusetts professor of English and Judaic Studies James Young has written: “It is little wonder that German national memory remains so torn and convoluted: it is that of a nation tortured by its conflicted desire to build a new and just state on the bedrock memory of its horrendous crimes.” Written in 1992, just prior to the completion of The Monument, Young’s observation still speaks to the predicament all countries face when attempting to create national responses in acknowledgment of crimes inflicted by the state upon its people. This past June, Canada’s House of Commons passed a Truth and Reconciliation Act, which operated as a long overdue acknowledgment of fault with the Indian Residential School system. The damage runs deep within the Canadian cultural landscape, rendering many unable to speak because of the complicated extent of the trauma. Do articulation and awareness really make a dent in ongoing human rights violations such as these?

The “defacements” of Confederate monuments in the southern states of the US in June 2015 were timely acts of utilizing monuments as valid sites of recasting memory and engendering response from the public. There is a definite need to bring these issues to the surface. When I spent time conducting research on American/Canadian artist Suzy Lake, I was struck by her commitment to social causes, a commitment that has been continuous through her career as she has related her investigations of subjugation, loss, estrangement, identity, and growth through representations of and on the body. Her exploratory, conceptual practice underscores the role of artist as social activist, artist as researcher, artist as mother, and artist as collaborator. Her dedication, Esther Shalev-Gerz’s dedication, among countless other artists and anonymous activists are the source and responsibility for establishing a place for historical revision by and in dialogue. In keeping, Shalev-Gerz said the following about the experience of opening up to an artwork: “It’s all different - how someone opens oneself to the inspiration of an artwork, and how one artwork can be the inspiration for the most fantastic thought to the most horrible thought and to the most futuristic thought about history.”

Esther Shalev-Gerz’s work, Portraits of Stories, is being shown in North America for the first time in the exhibition "Holding Ground” at The Wave Pool in Cincinnati until November 20. In December, her work will be included in the 1st Asia Biennial and 5th Guangzhou Triennial in Guangzhou, China.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Friedländer, Saul. “Trauma, Transference, and ‘Working Through’ in Writing the History of the Shoah.” History and Memory no. 4 (1992).

Shalev-Gerz, Esther, in conversation with the author, August 20, 2015.

Young, James. “The Counter-Monument: Memory against itself in Germany Today.” Critical Inquiry 18, no. 2 (1992): 267-296.

ANOUCHKA FREYBE

Masters in Art History from York University. Internships at the Neues Museum Weserburg Bremen, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, and the Art Gallery of Ontario. Worked in education and exhibition development at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. Volunteered in school programs, Education Department at the AGO, and Canadian Art Foundation's RAFF (Reel Artists Film Festival) Opening Night Committee. Contributor and researcher for the Introducing: Suzy Lake exhibition catalogue. Current co-chair for Gallery TPW's annual fundraiser, Photorama.

Work #950: BIRTH TO (NEAR) DEATH AND BACK AGAIN

In Four Parts

The fluidity of power—the idea that authority can be both effectively enforced from afar as well as allowed to fester quietly within—has been explored in much of my work over the course of my career. While the task at hand is to address the issue of “risk,” I’ve chosen to tackle this question by greatly ex-panding upon an artist’s statement accompanying four of my works that were presented together at the Robert Kananaj Gallery during the summer of 2015 to celebrate the gallery’s fourth anniversary. These works were created over the past five years—from the birth of a culture-defining method of social con-trol with centuries-long ramifications, to the acceptance of, over a brief period of time, the tyranny of aging (along with tangents about the death of the avant-garde and the trouble with selfies). This further elaboration and close reading of the four works both explores and exposes the political, psychological, and emotional implications of power dynamics from the macro (on a societal level) to the micro (on a cellular level). This closer examination reveals a continuity of spirit and an intellectual engagement supplemented by real-world (as opposed to art-world) experience firmly grounded in art history.

—1—

As a work of literary fiction, the first five books of the Old Testament (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy) may provide a gripping narrative, but in 1604 when James I commissioned a translation from Hebrew and Aramaic to consolidate regal authority his intent was never to lay out the blueprint for an equitable society, but to produce an officially sanctioned, standardized document to regulate daily life and act as a blunt force weapon entitling the sovereign the power to supersede the rule of law. By allegedly relying on the services of the leading literary lions of the day (Shakespeare et al.) to gussy up an otherwise dry narrative, the King’s political mission reached fruition. Work # 808: Leviticus (Updated) is the first in a series of large scale conceptually-driven photo-based works begun in 2010 after suffering a crisis of faith, that the future viability of art was something other than that of a diversionary caprice for the so-called one percent—a crisis actualized by the desire to kowtow to the limitless demands for the familiar and the safe and the conventional; a crisis triggered by the despair of witnessing in the late 1970s what little remained of the historical avant-garde devolve into a morass of triviality and disposable mass entertainment. To swipe a couple of lines from Michel Houellebecq, “at this stage we don’t give a damn about the reviews. It’s no longer there that the real decisions are made, [and] we’re at the point where success in market terms justifies and validates anything, replacing all the theories.” (I have my own theory about the late ‘70s collapse – having been a part of it—but that is fodder for a separate discussion.) We’ve reached a point in which an increasingly public debate (Bürger, Danto, Foster, Vargas Llosa et al.) questions whether art even continues to exist. From Manet forward to the beginning of the Reagan/Thatcher/Mulroney era, artists willfully maintained an antagonistic relationship with their patrons. And while every art student makes an unspoken pact with the notion of capitalist consumption, any engagement with or against the marketplace is a situation fraught with peril. I can think of no significant time during that century and a half before the late ‘70s when artists were as willing and eager to service the slumming diversions of the well-heeled as they are today. The death of innovation that followed the avant-garde’s collapse saw the advent of post-this and neo-that. It’s not for nothing that “In the Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century” (MIT Press, 1996) Hal Foster dismisses the “neo-s” as the “necro-s”.

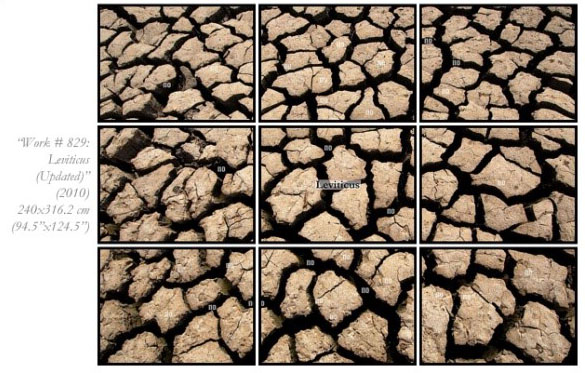

In Work # 808: Leviticus (Updated), the idea was to hit the reset button and return to the be-ginning. Relying on David Plotz’s exceedingly witty and acerbic “Good Book” (HarperCollins, 2009) as my guide, my “Bible for Dummies,” my “Coles Notes for Scripture,” allowed me to approach the inherent foreignness of these foundational texts as raw material and to respond to and contemporize a work in-troduced to the world by King James by reducing the words he authored to their visual essence. Work # 829: Leviticus (Updated) is enormous. It consists of a 228.6x304.8 cm (90”x120”) photograph of a drought-stricken riverbed chopped up into a framed grid of nine 76.2x101.6 cm (30”x40”) panels ran-domly covered with the word ‘no’ repeated twenty-four times. The source material’s narrative was in-tended as an instrument of rigid social control through behaviour modification and took the form of an exhaustive litany of prohibitions combining the ludicrous and the lethal, from the sumptuary to the sex-ual. My visual rendition of the document takes its laundry list of diktats and offers them up as a series of tiny but emphatic, foot-stamping no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no-s sprinkled like seeds across a desiccated landscape that will never allow anything to grow. Leviticus was the book that fun forgot; its only value has been to allow generations of sanctimoni-ous hypocrites the free rein to pick and choose their weapons of mass bullying. And like the book, the artwork that dares to speak its name is heavy and dour and negative, hung so low to the floor that it becomes an all-powerful, all-enveloping vehicle of oppression.

—2—

Accepting as its personal saviour the guiding spirit of Salò: 120 Nights of Sodom—Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1975 enumeration of abuse of power, corruption, sadism, sexual perversity, and fascism—Work # 864: The Nature of God (2013) is one work from a series that explores the outer limits of masculine behavior, which is traditionally still expected from the boy before he is considered to be fully a man. While I have long delved into the question of the “gay sensibility,” this is neither a trip down memory lane nor a retreat into the stereotyped suck-and-fuck paradigm. I'm positioning myself as an ironic spectator of this world of men ripped from the daily headlines, where the 19th-century notion of a romantic friendship is kicked into the gutter. With titles like Trailer Trash Terrorism, Behave Work Obey, Yes I Will Yes, Cell Block Bitch, Ash(And)Tray, and Shhh . . . (How to Conduct a Successful Interrogation—Lessons 1-20), this series of works is not intended for the faint of heart.

Cherry-picking at will from a variety of sources—the morning headlines, the official record of 20th century art, the signs and signifiers of the gay male underground has allowed me to explore the spaces between these charged relationships. What I do with this series is the opposite of aestheticize the gleaming muscleboy or explore the romanticism of male bonding. It is old news that the male body continues to be a provocation; ironically, a critique of masculinity has gone largely unexplored. Herein lies the challenge: it furthers the proposition examined in much of my work that it should be possible to be simultaneously hot and sweaty and critical and detached. It is desirable—even exhilarating—to ques-tion the givens of our cultural baggage while at the same time allowing ourselves to be wrapped in its brawny arms. Work # 864: The Nature of God allows that the rigour of discipline often morphs into the disciplinarian running amok. Notwithstanding the fact that this work has been described as ‘the water-boarding piece’ (which is an interpretation that I don’t dismiss), it is a multi-image cum-soaked force-feeding enacting either the predetermined choreography of an arcane sexual ritual or the resolution of cold-blooded revenge. That’s up for you to decide; it’s September and (reform) school is now in session.

—3—

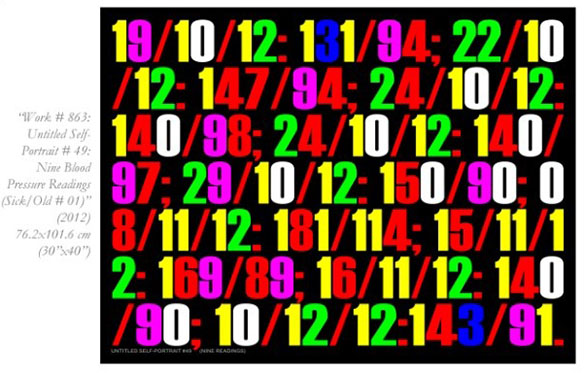

The seven rows of deceptively random, densely packed, brightly coloured and seemingly arbitrary numbers that fill the 76.2x101.6 cm (30”x40”) picture elude easy interpretation. The clue to unlocking the meaning of this secret code is partly revealed by the presence of “Untitled Self-Portrait #49 (Nine Readings)” along the bottom edge of the image. With study, the apparent randomness resolves into a series of dates and medical readouts; carnival-coloured though it may be, and written in a numerical language that only cardiologists would love at first sight, it is a work perhaps at its most personal and exposed because it addresses my own mortality.

As a darkly witty attempt at wresting control away from the terrors of aging, Work # 842: Untitled Self-Portrait # 49 (Nine Blood Pressure Readings) Old/Sick #01 (2012) is a work that grudgingly acknowledges my being granted a visa to enter the Republic of Oldmanland. After being diagnosed with a heart condition that required a surgically-implanted stent to open a blocked artery close to my heart, and thus narrowly avoiding a probable fatal cardiac event, a six-month stint in cardio rehab was man-dated. It’s not without a sense of irony that the author of this self-portrait fails to appear in any recog-nizable form. (A target blood-pressure reading should be anything below 140/90. During the period when this piece was being put together, the ‘high point’ (so to speak) was 181/114. This was moving into stroke territory.) At the most recent annual meeting with my cardiologist there was no mention of me as a person; rather, the evaluation was based entirely on my numbers. All of my numbers were be-low the desired targets. My electrocardiogram numbers looking good; my blood pressure numbers look good; my heart rate numbers look good; my cholesterol numbers looked good. With only having to rely upon minimal medications, lots of walking, and a decent diet I’ve been given a clean (if slightly diminished) bill of health—so there. There’s obviously a difference between quiet introspection and narcissistic self-admiration, be-tween mindfulness and histrionics, between documenting an experience after the fact and experience itself. There’s something charming about the humbled expressions on the faces of tourists posed in front of a wonder of the natural or built world, moved to such a degree that total strangers were asked to document the memory of what they just witnessed compared with the sensitivity-challenged, grinning idiots in front of a death camp episodes. Every moment, every experience, is reduced to having the same value as every other moment and experience. There’s something desperate and needy, something deeply anti-intellectual about not understanding the importance of an insightful experience because it’s been clouded by auto-infatuation. Karl Ove Knausgaard states that “only a poet would see the difference between poetry and poetry that resembles poetry [and] you were constantly on the verge of the insight that what you were doing actually had no value.” A quick search of Google for answers to “why I hate selfies” produced 6,090,000 results. This makes plausible the fictional encounter of a selfie taken in the Sistine Chapel where photos and video are forbidden: “God is right next to ME and he’s sticking his finger in my ear LMFAO!”—4—

A piece about the state of art as art, Work # 937: April 5, 2015 (My Bedroom) a 101.6x76.2 cm (40”x30”) is a mound of trash made up of dirt, and dust, and dog hair, and dead leaves swept up from my bedroom floor. Aside from everything else, it is a rather too gentle commentary full of Duchampian disdain for two unfortunate trends: sentimental pining over disaster and decay, and the hauling-piles-of-rubbish-into-gallery-spaces-and-calling-it-baroque practice among those armed with freshly-minted but pointless MFAs. (As an aside, does it need to be pointed out the Baroque was a reactionary response that arose at the behest of the Vatican in its counter-assault against the Protestant reformation? Then as now, reactionary times foster reactionary art.) Even though it’s tangential to the fact that if you go all squinty-eyed over this pointedly ugly pile of crap it begins to resemble the face of some hominid-like thing, it is a self-portrait in all but name. Notwithstanding a nod to Quentin Crisp’s brilliant fib that after five years the dust doesn’t get any deeper, the work operates against a backdrop of darker cultural significance to confront ageism – the last acceptable form of bigotry allowed to be voiced openly across all sectors of society, but most shamefully within the art world itself (that one of the edits from the KAPSULA writing workshop hosted by Gina Badger made reference to grumpy old men merely reinforces my contention in this regard.) The label for everything else that had been set aside resides in the visually whispered text ‘MY BEDROOM,’ embedded in the centre of the photograph—grounding itself as a self-deprecating auto-assault and a psychological marker of loneliness, depression, and their combined power to destroy.

It’s not for the lack of an alternative that I’ve expropriated control over a formal studio portrait from my boyhood and claimed it as my first self-portrait, repurposing it as my profile pic on various so-cial media sites. It’s assumed the photograph was specifically chosen by my parents from an extended session. They saw something in my pose—the slight sneer? the slight arch of my brow? the ramrod straight haughtiness?—that foretold this little boy from the late 1950s was never destined to be an archetypal man in a grey flannel suit.

Over the course of the past number of decades I was the little boy in the iron lung who survived most of the ravages of polio; made it through years of vicious and violent teenaged bullying almost un-scathed; escaped the genocide of AIDS by sheer dumb luck when living in New York City throughout the 1980s and ‘90s while thousands of my peers were dropping like flies; watching helplessly as my partner of twenty-five years went from robust, burly masculinity on our wedding day to a shriveled corpse after six months of being eaten alive by cancers so ravenous he didn’t stand a chance; but was finally nearly taken out by a silent genetic predisposition beyond my control. It’s the missing pieces implied by ‘surviv-ing most of,’ ‘made it through,’ ‘escaped,’ ‘watched helplessly,’ and ‘nearly taken out’ that are the seeds from which my art has be able to sprout.

BRUCE EVES

As a visual artist, Eves has been influenced by the theoretical issues raised by performance and conceptual art. This has been supplemented by experience as art director of the New York Native, chief archivist for the International Gay History Archive (now part of the Rare Books and Manuscript collection of the New York Public Library, and assistance programming director of the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC).

http://bruceeves.blogspot.com

THE WAITING GAME