Production:

EDITOR IN CHIEF / CAOIMHE MORGAN-FEIR

SUBSCRIPTIONS & DEVELOPMENT / YOLI TERZIYSKA

MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS / LINDSAY LeBLANC

DESIGN & ART DIRECTION / ZACH PEARL

Contributors

BOJANA VEDIKANIC

FRANCISCO-FERNANDO GRANADOS

HENRY CHAN

JESSICA SIMAS

SHANNON COCHRANE

PAUL COUILLARD

Cover Image:

LOREN SCUT

When I was five performed at Haight Gallery, Calgary

2012

Photo: Monika Sobczak, Performance Art Studies (PAS)

You are viewing: ACTING OUT 1/3, published in October 2014

CONTENTS

Meaning Through Movement

A MANIFESTO FOR PERFORMANCE

Commemorating the 10th Annual 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art

Featuring the photography of HENRY CHAN & reflexive texts by

BOJANA VIDEKANIC, FRANCISCO-FERNANDO GRANADOS, PAUL COUILLARD & SHANNON COCHRANE

The Act(s) of Looking

Cinematic Visions in The Act of Killing

by Jessica Simas

Prologue Meaning Through Movement

In this release, we venture off the beaten path to bring you a commemorative piece on 7a*11d, Toronto’s premier international festival of performance art. This annual, weeklong programme presents a range of efforts: residencies, lectures, special events and of course, performances. Launching its 10th iteration this October, the festival has favourably carved out a niche in both the local and international arts community, attracting a great number of participants and consistent press. In keeping with that tradition, KAPSULA is delighted to publish an exclusive photo retrospective of the festival, featuring the beguiling work of Henry Chan.

Instinctive, insistent, disarming; all words that accurately describe Chan’s cunning prowess for the elusive, documentary shot that is also “the image” of performance. Further, all are words that equally evoke the defiant spirit of our autumnal theme—ACTING OUT. This is not a coincidence. As a matter of fact, neither are the four performance manifestos that disrupt the photo essay.

Written by 7a*11d organizers and performance art ‘veterans’, these missives-on-a-mission are in themselves performative texts—mercurial and uncompromising. Much like the manifestos of modernist yore, each attempt to define or distill performance art slowly undoes itself, shaking off labels or parameters with vigor. Yet the honesty of these accounts instils a sense of urgency—to rattle pre-existing structures and, ultimately, produce change.

But, why not simply (re)make the reality you want to live in? Give or take some megalomaniacal delusions it all sounds simple enough. It certainly did to the former death squad leaders of the 1965 Suharto dictatorship in Indonesia. That is, when Joshua Oppenheimer asked them to re-enact their war crimes on film. Reeling with intrigue and revulsion, Jessica Simas takes us on a morbid thrill ride through the making of the documentary The Act of Killing, in which ex-paramilitary, self-proclaimed “gangsters” make their own filmic masterpiece, Born Free; shamelessly employing Hollywood tropes of mafia violence to heroic effect. In the process of exposing despicable ignorance, Oppenheimer also captures the cinema’s most dangerous capacity: to act outside the cinema. Pervasive and political, Simas shows how the mythos of the silver screen can quickly bleed out into the streets as living tragedy and somnambulant society.

The Hollywood indoctrination of Oppenheimer’s subjects is rare in its extremity. But, if your inner-cynic is already painting a picture of cineplexes lined with zombies in 3-D glasses, you’re not far off base. This inaugural issue of ACTING OUT is not only a series of reflections on breaking with convention , but a chain of provocations toward agency. “Acting out” ideally goes beyond misbehaviour or dissention, instead prompting meaningful responses—those that collectively map an engaged and critical dialogue on performing, and not strictly as a mode of art-making but also as a process of social and cultural mobility. The texts in this issue navigate such spaces of performance to reach conclusions about how we make meaning through movement. Cast aside your notions of tempers and tantrums. In our view, acting out is a thoughtful and effective mode of resistance.

And with that, before our sentiments flood your reading with a rose-coloured hue, KAPSULA gracefully exits. Read on, darlings, read on.

A Manifesto for Performance

Commemorating the 10th Annual 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art

Featuring the photography of HENRY CHAN & reflexive texts by

BOJANA VIDEKANIC, FRANCISCO-FERNANDO GRANADOS, PAUL COUILLARD & SHANNON COCHRANE

I met Henry Chan in 2004. I was working at the Images Festival and Henry showed up one day and volunteered to take photos of the festivities (mostly party shots, how does one take a photo of a film screening exactly?) Unassuming, Henry moved through the throngs of slightly tipsy party revelers at the opening and closing fêtes, snapping shots of filmmakers and punters together, arms slung over each other’s shoulders, red faced and comfortably tired from the adrenaline and the sponsored beers.

But, that’s just it. When Henry brought the discs of party pictures to the office several days later, they contained not a litany of flash-filled snapshots of drunk experimental film diehards at a typical closing event; but image after perfectly composed image of beautiful people with hips cocked at fashion angles, flushed with excitement and glowing from the inside, cavorting at the best party of the year. And he managed to do all this while making himself the most unlikely of party guests, meeting everyone and yet being hardly seen.

A couple of years later, I asked Henry if he would photograph the 7a*11d festival. It seemed to me that a man that could do what he did for the party shot would be more than able to find the ‘image’ in a performance. Since then the contribution Henry has made to Toronto’s performance art community and the art community in general (Henry has become the go-to photographer for just about everything) goes beyond impactful. After all these years, and Henry’s steadfast dedication to the genre, his work is making a pretty serious play for dominating the archive with its presence, and we wouldn’t have it any other way. Henry embodies the essential qualities of a great documentary photographer. He has stealth and style. But it is his interest in the work and the artists themselves - his pure quality of intention - which transforms the photo of the performance into an image of the work.

In the days after 7a*11d’s closing, when I watch the Facebook profile pictures of the festival’s participating artists switch to a photo of their work that Henry took like the split-flap display on the arrivals and departures board in a train station, I’m reminded of his talent. When Henry engages with an artist and takes more amazing photos of their performance than it is even possible to edit, I’m reminded of his generosity. I’m not sure, as a community, if we really know what to do to acknowledge and honour Henry’s work, but for this edition of Kapsula, in advance of the 10th edition of 7a*11d taking place from October 29-November 2, 2014, we offer this small photo essay of Henry’s work as a modest start.

You can also see a wealth of Henry’s images on the FADO Performance Art Centre website (www.performanceart.ca) and selected images from past editions of the festival on the 7a*11d blog (www.7a-11d.ca).

~Shannon Cochrane

ABOUT HENRY CHAN

(from the 7a*11d festival website)

Henry Chan has been documenting performance art in Toronto since 2006. He has photographed five of the ten 7a*11d festivals, the activities of FADO Performance Art Centre for the last 7 years, as well as events, exhibitions and performances at various venues including the Images Festival and The Power Plant. When he is not using a camera, Henry is crunching numbers and pushing paperwork as an accountant.

Untitled. Les Fermières Obsédées. 2006. 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art. Photographer: Henry Chan

Intra Muros 1. Martine Viale. 2012. FADO Performance Art Centre. Photographer: Henry Chan

Raaka–RAW. Pia Lindy. 2008. 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art. Photographer: Henry Chan

When it comes to performance art, it is perhaps less interesting to think about a definition of the term than to consider what it mobilizes. Why, for example, should a successful pop star like Lady Gaga feel compelled to declare herself a performance artist? Especially when my own experience using the term has led to so many blank expressions of incompr¬ehension (and so little economic reward)…

Performance artist? What is that?

Something unimaginable, and so the hapless questioner already has a task set before them: to expand their imagination to make room for this unimaginable, marginal other.

Never mind that Lady Gaga likely has only a limited awareness of the particular lineage I mean to cite when I call myself a performance artist. There is a network, certainly, but no union. No professional association will sue her for appropriating the term.

Is it pretention on Lady Gaga's part to call herself a performance artist? Perhaps, but if so, then that is also noteworthy. What is so remarkable about being a performance artist that to identify oneself in this way is tantamount to a declaration of self-importance?

Surely when Lady Gaga uses this term rather than a hundred others she might respectably claim—musician, celebrity, pop diva, fashionista—she is demanding for herself some breathing room, to do and be a musician, a celebrity, a pop diva, even a fashionista (and more), in ways that fall outside the norms of expectation. She is declaring an allegiance to something other than the currency of these familiar trails, to something not yet fully integrated into our daily imaginary.

This expansion is not necessarily what performance art achieves in actual practice, loaded down as it is by its histories and by the particular poverties of our collective hallucinations, but I like where it's going.

Speaking only for myself, I use performance art to create situations that might encourage me to expand my repertoire of behaviour, to break out of my habit world and also to call attention to things that I perceive all the time (tentatively, intermittently, constantly, urgently) but that do not appear to be solidly entrenched in public awareness. But that doesn't tell you anything, really, about what performance art is. Who cares?

If there is a reason to maintain this term, performance art, it is not because of what it has been, or even because of what it is. It is, rather, because of the possible worlds the term opens us up to imagining and becoming.

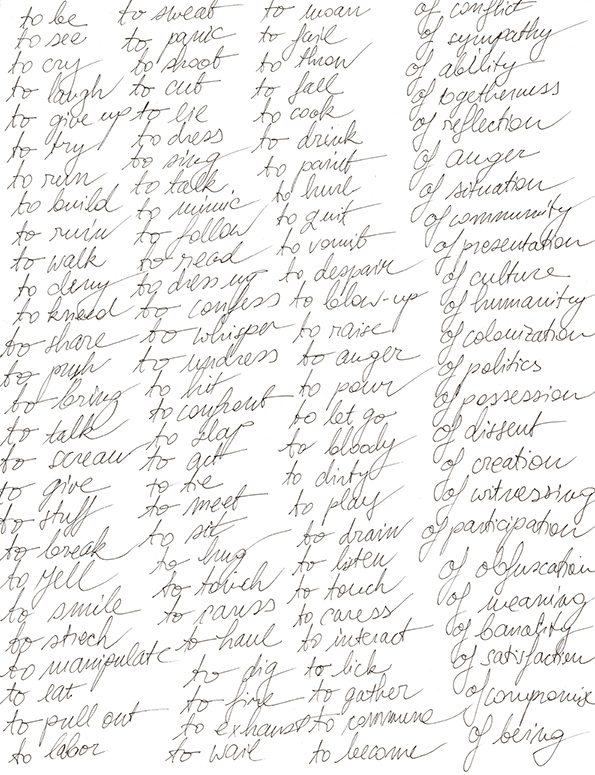

— Paul Couillard

Ranchero. Jamie Mcmurry. 2010. FADO Performance Art Centre. Photographer: Henry Chan

Performance Connection. Irma Optimist. 2010. 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art. Photographer: Henry Chan

— Bojana Videkanic

Invert Two. Hugh O’Donnell. 2010. FADO Performance Art Centre. Photographer: Henry Chan

Home. Rachel Echenberg. 2012. 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art. Photographer: Henry Chan

Freeing the Mind. Anna Kalwajtys. 2012. 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art. Photographer: Henry Chan

Performance art was a chance encounter on a breezy Vancouver summer day.

I was a twenty-year-old student in my first year of art school, training to become a painter. On my way to meet another boy, I walked past the magazine shop on Commercial Drive. The image of a figure with short dark hair, dressed in black, abstracted by a translucent layer of dripping, bloody crimson seized my gaze. It was a photograph of an action by Rebecca Belmore on the cover of a magazine. She had flung a bucket of blood at the lens after coming out of the water. One of the headlines read: PERFORMANCE ART NOW: Vancouver vs Toronto. I bought it and went to meet my date.

Over dinner, I spilled butter chicken sauce on my shirt. I tried to wash it off; it made the stain fainter, larger and wetter. We walked to the beach and sat under a tree to let it dry. I brought out the magazine and started reading it to him. Fascinated, I narrated Randy Gledhill’s account of performances from 7a*11d:

She honks a rubber bicycle horn, then begins pronouncing aloud a rhyming stream of nonsensical phonetics. Then in rapid succession: …neuro performance, schizo performance, masochistic performance, sado performance… cryptic performance. The artist vanishes under the table.

He listened politely, but struggled not to roll his eyes. He wrote poetry. I was in love.

I became a performance art groupie a couple of months later, going to any event I found out about. Eventually, I started meeting people and felt a sense of belonging I had not quite found anywhere else. One night, Naufus Ramirez-Figueroa called me to ask if I would be interested in participating in a performance workshop taught by him and Irene Loughlin at Gallery Gachet. I jumped at the opportunity and did my first piece. There were stained shirts and hickeys.

We, performance artists, often refuse to give a definition when asked to talk about the form. But as performance has entered a period of public, sometimes mainstream, attention, it seems important to say:

Performance is different from any other art form I can think of because it stages the labour of the artist. When you paint, take a photo, make film or build a sculpture, the time and sometimes the space of the creation of the piece is different from the time and space of the presentation of the piece. In performance, the time and space of creation are simultaneous with the time and space of presentation of a work.

That being said, performance art is not just a way of working, or a (very precarious) career choice, but also an incalculable way of belonging with people who might become your family, or with whom you may have nothing else in common. This is some comfort to those of us who have been disillusioned and hurt by nationalism.

— Francisco-Fernando Granados

Untitled. Irene Loughlin. 2012. 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art. Photographer: Henry Chan

Untitled. Gustaf Broms. 2013. FADO Performance Art Centre. Photographer: Henry Chan

The Impossibility of Understanding Yourself Out of Context:

A Performance Manifesto

Shannon Cochrane

Since 2011, I have been engaged in an on-going collaborative project created by Ame Henderson (choreographer, dancer) and Evan Webber (performance creator) with Jacob Zimmer (theatre artist and director), Malcolm Sutton (writer), Frank Cox-O’Connell (actor, theatre artist) and Sherri Hay (visual artist), entitled How To Work: a Performance Encyclopaedia. In a nutshell, How to Work subjects the tasks of writing and research to the rigours of collaborative performance-making. In each iteration (there have been three so far) the group of us, as artist-researchers, attempt to record (i.e. article in the fashion of an encyclopaedic volume, complete with cross references) all of our most useful and important experiences of making and viewing performance through the words and terms we habitually voice, over a designated time period of office hours. This process yields a published document, a performance in the shape of a book.

On the first day of a working period, we make a master list of the current words we want to article. On the first day of the first iteration, I noticed that I was the only person in the group who added “performance art” to the list. Perhaps, I thought, our group’s apparent common ground is not all that common. When I point this out, Frank makes a joke that perhaps through this process I will come to realize that my hallowed label (performance art) is hollow. I pretend this doesn’t bother me, but what I really wish I had said was, “Spoken like theatre.”

Frank might think that he has no stake in the definition of “performance art” (in general, or how it relates to other live arts) and it is only for me to define. But, in rejecting it, he exposes this definition, the one that is yet unwritten, as a sticking point between our tribes, raising to the tender surface the distance between us. Instead of emancipators, the categories we choose to define our work, and thereby ourselves, are obstacles and stifling limitations. I have made many works of performance art in the theatre, but the container is only context, not a way to understand process. If performance is just a word, what exactly is performance art?

Spanish artist Esther Ferrer has said that performance art has as many theories as artists. She follows that up with the wise instruction that all you need to know about performance art you can learn in three minutes. With these two sage pieces of advice in mind, instead of belaboring a manifesto of performance art here, I might simply invoke the sardonic line Toronto legend Keith Cole sends when you email him to ask for a brief biography: ask around.

We were only given the space of 300 words to write a personal manifesto of performance art, a limit I have already exceeded not saying anything in particular, so instead I will end by proposing an exchange. If you really want to know what I think performance art is, email me at knowmanifesto@gmail.com, and I will send you an opinion that feels right on that day. This way of delivering a manifesto will be—like performance art itself—a nomadic, polymorphous, radically flawed work-in-progress.

THE ACT(S) OF LOOKING:

Cinematic Visions in The Act of Killing

The Act of Killing (2012, directed by Joshua Oppenheimer) is a film that, at the most rudimentary level, amalgamates footage shot between 2005 and 2011 of former Indonesian paramilitary leaders who were key figures in the 1965-66 anti-communist purge. The massacre followed a failed coup by the PKI (Indonesian Communist Party) and was carried out by the “New Order” military dictatorship of Suharto, which was backed by US, Australian and British administrations. In less than a year, hundreds of thousands of suspected communists were killed—this included (but was not limited to) union members, landless farmers, intellectuals and ethnic Chinese.It is estimated that between 100,000 to 2,000,000 suspected communists were exterminated between October 1965 and March 1966. (Lowell Dittmer, “The Legacy of Violence in Indonesia,” Asian Survey 42 (2002): 542.)[1] Now, almost fifty years after the events of 1965, former death squad leaders live with impunity, and newer paramilitary organizations such as Pancisila Youth continue to thrive in their shadows. After spending several years in Medan, North Sumatra, speaking to survivors of the Suharto regime, it is suggested to Oppenheimer that he meet and document the perpetrators of these crimes, rather than the survivors, in order to understand the still lingering vibrations of right-wing militancy. Since the perpetrators consider themselves “gangsters,” or heroic “free men,” they respond enthusiastically when Oppenheimer asks them to recreate scenes about the killings they once carried out in whatever ways they choose.

In an often surreal and unsettling manner, the protagonists, who glorify Hollywood cinema, employ the strategies of various narrative genres—such as gangster films and musicals—in order to triumphantly restage scenes of murder for their own film within The Act of Killing, entitled Born Free. This secondary production initiates a dialogue with a brutally violent four-hour anti-communist propaganda film titled Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September PKI (G30S) (1984, directed by Arifin C. Noer). For fourteen years after its release until Suharto resigned in 1998, this film was broadcast on Indonesian television and in all cinemas.Joshua Oppenheimer and Michael Uwemedimo. “Show of Force: a Cinema-Séance of Power and Violence in Sumatra’s Plantation Belt,” Critical Quarterly 51 (2009): 85.[2] Consequently, it played a major role in perpetuating the “official history” of 1965. This strategy—to intertwine the space of cinema with death and violence—seems to crop up at several moments throughout The Act of Killing. In one sequence, perpetrator and “star” of Born Free Anwar Congo reminisces about Medan Cinema, a theatre that was central to paramilitary corruption due to their involvement with scalping rings. After watching films starring Elvis Presley and Sidney Poitier, Congo explains how he and his fellow death squad leaders would often leave the cinema dancing, yet the location where he would carry out a number of killings was located directly across the street.

From this initial observation, it would appear as though The Act of Killing ruminates upon the pervasive, even politically dangerous, nature of cinema itself. However, by strategically mobilizing the devices inherent to cinema, in addition to considering the impact of trauma theory, the politics of documentary and the ethics of reenactment, The Act of Killing ultimately functions to expose the profound critical potential in acts of looking. An analysis of this film may demonstrate how a more imaginative, radical approach to filmmaking can produce the tools necessary to uncover new forms of knowledge about historical violence and wider, global systems of injustice.

In Cinema I, Gilles Deleuze creates the foundation for cinema—defined as blocks of movement comprised of images and signs—claiming that it literally “intercuts” with philosophy, enabling the possibility for cinema to act as an immanent driving force in the real world.Gilles Deleuze, Cinema I: The movement-image, trans. Barbara Habberjam and Hugh Tomlinson (London: The Athlone Press, 1992), 1.[3] This is achieved by harnessing the movement-image, which is the mobile section of images existing between cuts that reproduce universal movement.Ibid., 6.[4] The movement of the camera itself, in addition to the obvious movement of people and things on screen, emancipates the essence of movement by transcending human perception. The movement-image also expresses time indirectly because a film can take place over a number of hours, days or even, in the case of The Act of Killing, years.David Martin-Jones, Deleuze, Cinema and National Identity: Narrative Time in National Contexts (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006), 20.[5] Consequently, the movement-image must work in tandem with the time-image, a concept developed by Deleuze in the context of post-war Europe. The time-image began to complicate the movement-image as films emerged from shattered nations by deploying a fractured, nonlinear metanarrative within a more linear structure established by the movement-image.Ibid., 2.[6] In this regard, the legitimacy of a singular, linear narrative that assumes a cause-and-effect relationship between historical events can be put under pressure. For Deleuze, the notion of time is opposite to the notion of the actual or the objective; it is wholly virtual, or subjective, which renders the experience of selfhood as durational because the subject is constantly morphing and changing throughout time.Gilles Deleuze, Cinema II: The time-image, trans. Robert Galeta and Hugh Tomlinson (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 86.[7]

When considering the movement- and time-image in combination, the possibilities for cinema are opened up to push the boundaries of representation. Accordingly, The Act of Killing elucidates the durational nature of real-world space-time by playing with the processes of organizing (grounding) and of consistency (ungrounding), respectively. A sequence depicting Herman Kato, a Pancisila Youth leader, on the set of Born Free during a rehearsal take exemplifies how The Act of Killing succeeds in consciously exposing its own grounding narrative. As an elaborately choreographed dance routine occurs, Kato describes an evening at Medan Cinema, but it is completely unclear whether this took place recently or decades earlier. This is also true of the opening sequence, where the dancing women emerge from the mouth of a giant fish-shaped structure. It quickly becomes apparent that they are on a film set when a dramatic cut reveals more dancers amidst a waterfall, and a disembodied voice shouts, “These are close-ups!” This marks the first rupture between what can be considered the film itself (The Act of Killing) and the film-within-the-film (Born Free) that creates a spatio-temporal zone of indistinction.Deleuze, Cinema II, 47.[8] The idea that a narrative cannot reliably convey an idea with conviction is also explored within the filmic narration itself when Congo and Kato discuss the structure of Born Free. For them, the logical sequencing of events need not apply as they determine that the brutal opening sequence involving decapitation should remain, even though that character will later appear with his head intact. “The scene exists in a time tunnel,” states Congo. Although Congo comes to this conclusion to serve his own ideological purpose, this sequence highlights the complicated status of linear, traditional narrative, which positions The Act of Killing as an experiment challenging the rigid relationship between the spaces of memory and historical time.

Additionally, Oppenheimer often employs open-form shots that deemphasize the frame during sequences of Born Free, and closed-form shots that create carefully composed, almost theatrical frames found in the more typical “documentary” portions of The Act of Killing. By subverting these framing tactics, the viewer is left with the task of negotiating between “real” and “imaginary” spaces. The staggering conflation of filmic genres also creates a rupturing effect when combined with an almost episodic use of narrativity. Different filmic genres, shooting locations and character traits flow in and out of one another with no pattern or explanation; for example, the image of a Congo as a cowboy in the jungle cuts rapidly to a shot of Kato vigorously brushing his teeth in a bathroom stall. The role of colour also becomes significant in Born Free. As opposed to being used deliberately by the director as an affective strategy, the perpetrators choose to over-saturate colour in their film, as when Congo chooses to wear a vibrant pink cowboy hat in one of the interrogation room scenes. For them, exaggerated colours render the film more film-like and create the “colour-image” that Deleuze describes to be so potent.Deleuze, Cinema I, 118.[9]

Although movement-images in The Act of Killing do establish a loose narrative trajectory, the film cannot be considered an example of narrative cinema proper. Therefore, when investigating the broad formal properties that were initially applied to New Wave cinema auteurs, a Deleuzian analysis can only go so far. The Act of Killing cannot even be considered an example of “minor cinema,” wherein marginalized or minority groups seek to create a new sense of identity through experimentations with the moving image.Martin-Jones, National Identity, 6.[10] This film is technically not a product of marginalized peoples, as Oppenheimer is credited as the director, and the question of violent, suppressed national histories does not factor into this definition. As such, The Act of Killing is less concerned with immediately constituting one homogenous national identity than it is with highlighting the fluid, decentered process by which a subject can attempt to come into being. This process, which exists across historical time, is where the larger potential in The Act of Killing lies for individual subjects. Considered as if it were a Deleuzian “sensation,” that infra-thin moment of recognition, the film within a social, historical context may in fact be that infra-thin moment of emancipatory confrontation between the horrific past and regenerative future.Deleuze, Cinema I, 62.[11]

The concept of witnessing then becomes crucial. Rather than constituting a passive act of looking, the witness is able to experience an active, often unwanted engagement with the traumatic. The formulation of the affection-image has been important in terms of understanding how the face is the surface upon which “pure affect” coagulates, and is expressed through framing, cutting and montage.Ibid., 103.[12] Although useful, this definition does not factor in the larger stakes of how a perpetrator might witness violence and how this could weigh upon a personal, even national consciousness. The Act of Killing, then, is demonstrative of something that may be called the trauma-image: a twofold process whereby the subjects—the perpetrators, in addition to the viewers watching The Act of Killing—are, together, at the threshold of multiple visibilities that are constantly unraveling. Only by reenacting and re-watching their filmic project do the perpetrators ultimately come to terms with the weight of their crimes. In turn, the striking visuality of The Act of Killing allows the viewer, most significantly the Indonesian viewer, to confront historical violence as it creates the conditions for powerful subjective interpretation. For Roland Barthes, traumatic photographs are powerful because they have the ability to eradicate speech, signification and connotation, as opposed to shocking photographs that essentially communicate nothing.Roland Barthes, “The Photographic Message,” in A Barthes Reader, ed. Susan Sontag (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983), 209-210.[13] Yet a photograph, although certainly capable of fostering an affective viewing experience, is merely a singular cut in space and time. The stakes involved in this particular kind of viewing can be considered preemptive to the cinema due to the notion of the frame. The frame as an “act of delimitation” makes the gruesome content found in representations of war even more unsettling because the viewer is brought within proximity of the event, but remains at a fundamental spatial and temporal distance from it.Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (London: Verso, 2009), 67.[14] Even Congo identifies that only by watching traumatic cinematic depictions of Nazi war crimes can people affectively see power and sadism, which is why Born Free must take the form of a film. In The Act of Killing, then, the trauma-image is born out of the framing of the film-within-the-film (Born Free) that creates this distance for the viewer.

The trauma-image is intensified when roles are reversed and Congo, the “Real” perpetrator, plays the role of a victim being interrogated while the camera lingers on his face. Suddenly, the director calls “cut,” and Congo remains on screen experiencing a kind of period rush, the all-too-real feeling that he is momentarily reliving an act of killing, with the viewer simultaneously caught between the radical transitions from Born Free to The Act of Killing.Sven Lütticken, “An Arena in Which to Reenact,” in Life, Once More: Forms in Reenactment in Contemporary Art, ed. Sven Lütticken (Rotterdam: Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, 2005), 42.[15] The scene then cuts dramatically back to the misty waterfall and elaborately choreographed dance from the opening sequence, as if to clasp a filter of representation on top of the camera lens to distort the traumatized Congo. However, the viewer is aware that they are watching an elaborate fiction, and is unable to reconcile the movement-image with the time-image. The belated impact of trauma on the subject becomes visible as the camera lingers on Congo, although his trauma remains un-owned and thus unknowable for the viewer. This experience intensifies even further when the viewer watches the perpetrators watching the playback of Born Free on a television screen. By meditating on the screen-within-the-screen, the viewer is distanced even further from the original trauma, fostering a more potent trauma-image.

The problem remains that The Act of Killing is categorized as a documentary. If it strictly adhered to this definition, it would completely negate its Deleuzian credibility by succumbing to the grounding, purely linear narrative. However, the recent reemergence of documentary in contemporary art can help elucidate how The Act of Killing challenges the previously believed truth-telling agency of this category. First, the process of “documenting” must be understood as constantly undergoing change. As Michel Foucault suggests, the “enunciative” function of the archive is essentially the collection of different “statement events” that contribute towards an understanding of something.Okwui Enwezor, “Documentary/Vérité: Bio-politics, Human Rights, and the Figure of “Truth” in Contemporary Art,” in The Greenroom: Reconsidering the Documentary and Contemporary Art #1, eds. Maria Lind and Hito Steyerl (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2008), 93.[16] When translated back into another kind of archive—the cinematic screen—a “statement event” may occur in the form of documentary; however, it should by no means be taken to be a singular truth.Ibid., 94.[17] A film such as 40 Years of Silence: An Indonesian Tragedy (2009, directed by Robert Lemelson) claims to reach this kind of truth by striving to create a surrogate “reality” that urges the viewer to identify with the subjects on screen. This is especially problematic because the film relies on a sympathetic engagement with survivors of 1965 by, for example, using an overtly Westernized score and featuring commentary by American anthropologists throughout the film.

However, The Act of Killing completely works against this model by denying the viewer access to historical context. Except for a paragraph of text at the beginning of the film outlining the initial proposal set forth by Oppenheimer, it deliberately avoids conveying a historicized account or moralizing message. There is no score, no overarching commentary, and no suggestion that the perpetrators are ciphers of pure evil. Although the film is embedded within a discourse of human rights (Oppenheimer is also an academic and activist), the film decries the kinds of representations that Susan Sontag discusses in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), with Born Free functioning as another layer removed from 1965. With this in mind, The Act of Killing cannot be categorized as narrative cinema, nor can it be considered an example of documentary. Even further, it cannot be considered “post-documentary” because it does not radically alter movement- and time-images and strip away narrative completely, whereas a work such as Western Deep (2002, directed by Steve McQueen) does.T.J. Demos, The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary During Global Crisis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 38.[18] It may be more adequate to label The Act of Killing a “postmodernist docu-drama,” where notions of historical truth and fiction rub up against one another in order to suggest that any kind of representation is inherently unstable.Janet Walker, “The Vicissitudes of Traumatic Memory and the Postmodern History Film,” in Trauma and Cinema: Cross-Cultural Explorations, eds. E. Ann Kaplan and Ban Wang (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004), 125-126.[19]

As much as The Act of Killing thematizes looking and the importance of bearing witness, its complex structure, forged by the fictitious/non-fictitious nature of Born Free, asks the viewer to do more intellectual work than a Hollywood film or traditional documentary. By exposing the claims to truth made by visual documents of violent war and trauma, the film insists that memory itself is never static or objective; it is interpretive and subjective, even operating cinematically. The evidentiary nature of photography is therefore questioned as the entire project relies on the play between fiction (Born Free) and nonfiction (the events of 1965) in order to question the ways in which subjective experience, historical narratives and films are constructed. On a macro scale, it has the potential to suggest how Indonesia is tied to a larger, global system of violence and oppression that deserves further critical attention.

While acts of looking are crucial for the perpetrators and the viewers of The Act of Killing, the act of acting—or, more specifically,

After Born Free wraps, both the narrative structure and viewing subjects break down together when Congo is unable to bear the significance of returning to one of the locations of his killings. He is visibly distraught, and suffers from fits of dry heaving. At the same time, there is no clear resolution for the viewer. Deleuze becomes instrumental once again for demonstrating how the notion of “eternal return” is not simply a mythical copy of a past event, but a productive, decentred mediation of that event. He writes:

It is repetition which ruins and degrades us, but it is repetition which can save us and allow us to escape from other repetition […] To the eternal return as reproduction of something always already-accomplished, is opposed the eternal return as resurrection, a new gift of the new, of the possible.Deleuze, Cinema I, 131.[23]

In these terms, reenactment may be understood as something outside of repetition, reproduction or simulation; perhaps it can be considered an ongoing epilogue with no clear endpoint

.Another question remains for the viewer that involves the stakes of authenticity and intentionality: is The Act of Killing just one giant act? And even if it is, does it matter? Indeed, Oppenheimer defends his method of “archeological performance,” whereby the routines of the massacres conveyed through the grammar of reenactment initiates the synchronized processes of downward “historical excavation” and upward “histrionic reconstruction” that can create the conditions for a plurality of responses.Oppenheimer, “Show of Force,” 103.[24] But another way to interpret The Act of Killing is through the notion of “delegated performance,” whereby contemporary artists hire nonprofessionals to perform as part of a larger project that follows parameters set by the artist, as exemplified by British conceptual artist Jeremy Deller.Claire Bishop, “Delegated Performance: Outsourcing Authenticity,” October 140 (2012): 91-93.[25] Often, the rhetoric of offshore outsourcing is subverted: whereas big businesses outsource to decrease risk, artists delegate people inside or outside their own socioeconomic groups to increase the unpredictability of their project, even risking failure, in order to reveal the stifling effects of, for example, globalization.Ibid., 104.[26] For some academics and activists, The Act of Killing would be flawed from the start because the viewing subject, assumed to be Western, would succumb to the pitfall that identities are determined on the basis of difference, or “are-nots,” which has become socialized as the norm.Butler, Frames of War, 142-43.[27] This is predicated upon the fact that the entire cast and crew of The Act of Killing fall outside the socioeconomic category occupied by Oppenheimer.

Of similar interest would be the film La Commune (Paris, 1871) (2001, directed by Peter Watkins), which stages media coverage surrounding the Paris Commune in the style of documentary to reclaim its radical politics for contemporary French society. La Commune could be subject to similar scrutiny as Watkins hires a number of immigrants from North Africa to play the Communards. However, in both La Commune and The Act of Killing, the subjects on screen become symbolic as much as they are individualized, because the devices of cinema help to blur the tense lines that separate the spontaneous from the scripted, and any singular author is negated outright.Bishop, “Delegated Performance,” 110.[28] As a result, both of these films succeed in demonstrating how reenactment on the cinematic stage can produce unthinkable, potentially liberating results.

Although the copious amounts of media attention surrounding The Act of Killing has made it well known in North America, it is crucial to note that the film has evaded censorship and continues to be screened throughout Indonesia. Yet unlike Pengkhianatan Gerakan 30 September, The Act of Killing is not meant to invoke immediate political action because it exists outside the category of political propaganda. Regardless of its classification, The Act of Killing urges all of its participants to look again and again. As it moves through time, its impetus is both visible and invisible. By exposing itself as a cinematic project, it effectively retreats back into the screen waiting to be unearthed again later. “Don’t get so into it,” Kato tells Congo as he struggles to regain composure after they film the interrogation scene, “don’t think too much about it.” This reaction could be directed towards the viewer just as much as Congo himself. Either way, it is an impossible command.

Footnotes:

- It is estimated that between 100,000 to 2,000,000 suspected communists were exterminated between October 1965 and March 1966. (Lowell Dittmer, “The Legacy of Violence in Indonesia,” Asian Survey 42 (2002): 542.)

- Joshua Oppenheimer and Michael Uwemedimo. “Show of Force: a Cinema-Séance of Power and Violence in Sumatra’s Plantation Belt,” Critical Quarterly 51 (2009): 85.

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema I: The movement-image, trans. Barbara Habberjam and Hugh Tomlinson (London: The Athlone Press, 1992), 1.

- Ibid., 6.

- David Martin-Jones, Deleuze, Cinema and National Identity: Narrative Time in National Contexts (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006), 20.

- Ibid., 2 .

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema II: The time-image, trans. Robert Galeta and Hugh Tomlinson (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 86.

- Deleuze, Cinema II, 47.

- Deleuze, Cinema I, 118.

- Martin-Jones, National Identity, 6.

- Deleuze, Cinema I, 62.

- Ibid., 103.

- Roland Barthes, “The Photographic Message,” in A Barthes Reader, ed. Susan Sontag (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983), 209-210.

- Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (London: Verso, 2009), 67.

- Sven Lütticken, “An Arena in Which to Reenact,” in Life, Once More: Forms in Reenactment in Contemporary Art, ed. Sven Lütticken (Rotterdam: Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, 2005), 42.

- Okwui Enwezor, “Documentary/Vérité: Bio-politics, Human Rights, and the Figure of “Truth” in Contemporary Art,” in The Greenroom: Reconsidering the Documentary and Contemporary Art #1, eds. Maria Lind and Hito Steyerl (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2008), 93.

- Ibid., 94.

- T.J. Demos, The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary During Global Crisis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 38. J

- anet Walker, “The Vicissitudes of Traumatic Memory and the Postmodern History Film,” in Trauma and Cinema: Cross-Cultural Explorations, eds. E. Ann Kaplan and Ban Wang (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004), 125-126.

- Homay King, “Born Free? Repetition and Fantasy in The Act of Killing,” Film Quarterly 67 (2013): 32.

- Jennifer Allen, “Einmal ist keinmal: Observations on Reenactment,” in Life, Once More: Forms in Reenactment in Contemporary Art, ed. Sven Lütticken (Rotterdam: Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, 2005), 183.

- Lütticken, “An Arena,” 19.

- Deleuze, Cinema I, 131.

- Oppenheimer, “Show of Force,” 103.

- Claire Bishop, “Delegated Performance: Outsourcing Authenticity,” October 140 (2012): 91-93.

- Ibid., 104.

- Butler, Frames of War, 142-43.

- Bishop, “Delegated Performance,” 110.

JESSICA SIMAS

is an academic and writer who has curated exhibitions in Toronto and

London, UK. Recently, she completed her MA thesis on dance and the

moving image at University College London, under the supervision of

Professor Briony Fer.