These are some thoughts arising after the opening reception for Vector Fest 2018: Born Digital, for the eponymous exhibition at InterAccess (950 Dupont St. Unit 1) featuring works by Adam Basanta, A.M. Darke, Joseph DeLappe, Judith Doyle, Ann Hirsch, Chris Kerich, and Lu Yang. This blog won’t engage with all of the works in the show, but is a short piece of experimental writing responding and in parallel to some of the ideas in the exhibition.

“I look at my bare feet on the tiles in front of me and think: Those are her feet. I stand up and look in the mirror and think: There she is. She’s looking at you. Then I understand and say to myself: You have to say she if it’s outside you. If your foot is over there, it’s there away from you, it’s her foot. In the mirror, you see something like your face. It’s her face.”

Lydia Davis, “Examples of Confusion,” in Almost No Memory (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1997).

You shouldn’t tell anyone your social insurance number, you shouldn’t. As for me I didn’t have to do anything to get one, just rolled out quietly. For others it’s an almost-insurmountable mess of precarity and travel and administration and money. A SIN is an unfinished waltz:

dun dun dun, dun dun dun, dun dun dun (“SIR!” my dad finishes, a leftover from his days in the reserves).

… … …

Three morse esses, hissing like the sticky guttering pennant of a forked pink tongue.

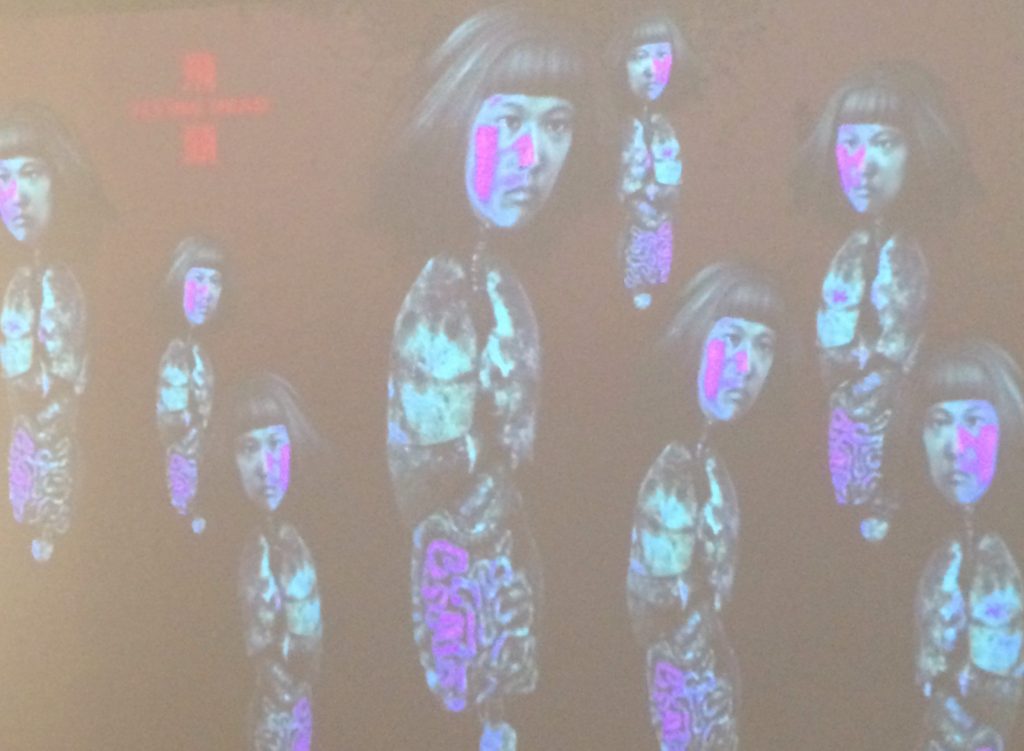

Along a human face on a pale blue screen, a bright green line scans, searing. The caption below reminds us that a 3D scanner is a device that collects data on an appearance, making a 3-D model. Rendering falls into place in lines up its legs, building a body, a model which can be stretched and manipulated. Steadfastly moving up the body, we see into cross-section: bones and muscle and tendon and sinew. Does a rendering need bones? It has bones because we have bones. It has bones because we want it to look like us. Throughout Lu Yang’s Lu Yang Delusional Mandala, the newborn 3-D model morphs fluidly across genders and bodies. They lumber and stagger, three copies dance in unison. Their skin and bones fall away until they are only a head, until they are only rhythmically moving lungs, until they are a bumping heart, a twitching intestine. Near the end they are a neon cart carrying a coffin, they are blinking lights, they are blowing billowing curtains of hair off their nose. It’s hard not to identify with a 3-D model of ourselves. Still, it is outside of you. As Lydia Davis insists, you have to use the third person. Those are their teeth. A digital child: that is their intestines.

Anyone who has created an avatar knows the push-pull of this identification. Creating a virtual body with which to emerge from cryogenic stasis, fight off irradiated beings, and find my missing son, I feel a mix of competing desires. Is she an ultimate self, or a new persona, or something different altogether? Am I? In her exhibition Tomorrow People at Oboro last year, Skawennati’s piece Generations of Play spoke about a doll-like identification with an avatar through an industry-made Barbie, a 3-D print of her Second Life avatar, and a handmade cornhusk doll. She draws a connection between her early analog “gaming” and her avatar as a “a virtual representation of herself, envisioned for the future.”[1] Instead, I want distance. My avatar is not only stronger than me and more able to pick a lock than I am, but her hair is long and a different colour. I give her a scar, and freckles. I do not give her my name. Yet I can still see myself in the largeness of her body, in the colour of her eyes. I take credit for her improving navigation skills and mourn her multiple deaths.

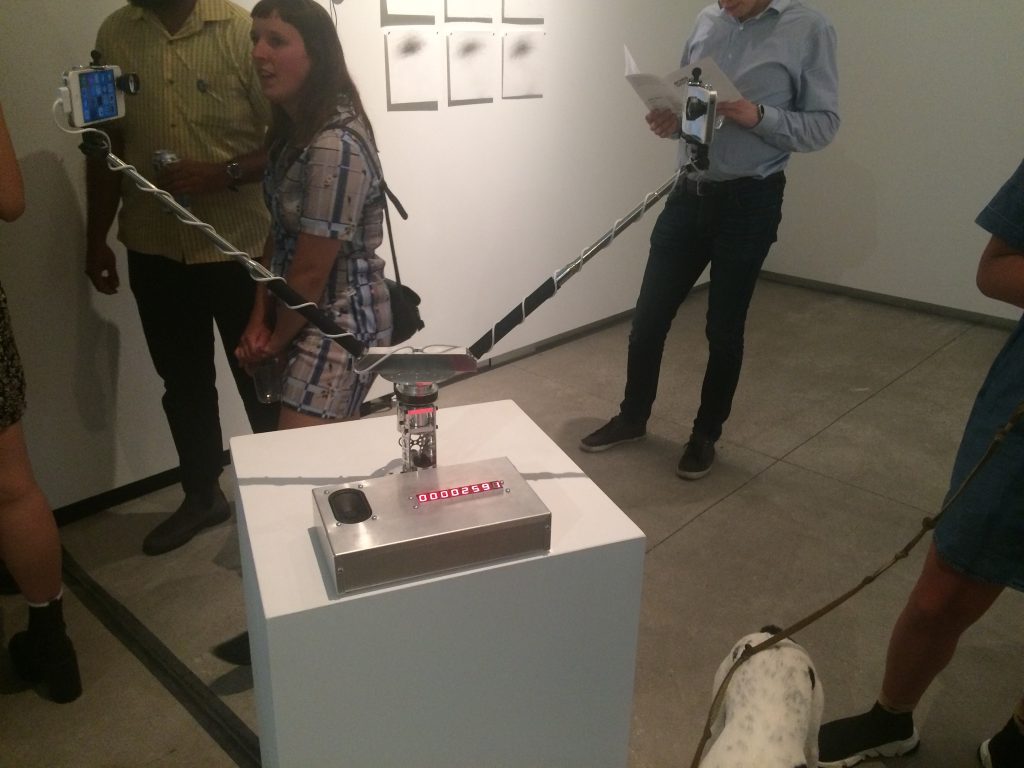

In Adam Basanta’s A Truly Magical Moment, two iPhones on selfie sticks face one another. Pairs of viewers, soon to be dance partners, connect to the phones through FaceTime, one to each. We share a magical moment for around a minute. Our partner’s face remains in focus while the room spins around us at top speed, aided by the whirling cameras until it slows and stops. I feel as though I should be laughing, stumbling at the end into the other’s arms. I am not laughing, I am not in anyone’s arms. The digital counter nearby ticks up one point and dance 00002591 is complete. The piece evades a one-note critique of the current digital distance, though. I do feel a tenderness, a closeness. There is a certain vertigo of seeing the room spin around behind my partner. It is no replacement for real dizziness. (Though I wonder: are those moments in life always truly magical? Something about them feels contrived, still.) That is her face, not mine, on the screen. I am a third wheel, involved only by proxy. Grasping at some of the trace centrifugal chemistry spinning off a giddy dance between two phones.

To identify is to make the same. It is an active process, a drawing of lines. They look so much like their parent, we coo with amazement. Does this attribute affinity, belonging, possession? He tells me:

“When I hit 35 or so I started clearing my throat exactly like my dad

I hate it

A sound that annoyed me for my whole childhood”

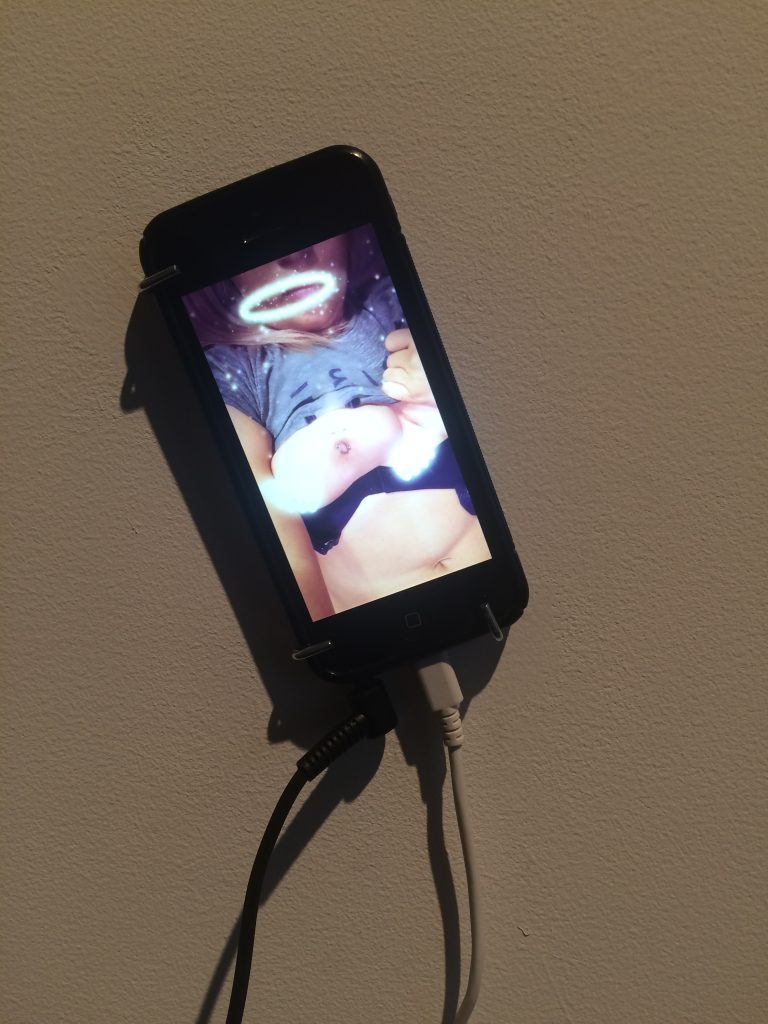

Projecting and identifying, forward and back. But what of our digital children, who we have more of a direct hand in creating? What of their chubby glitching fingers (count to 10, five on each hand), their digital births? Within them, the unspoken biases of their makers and their own technological errors surface. What happens when they look back and identify you? A.M. Darke’s ar+ show speaks to these malfunctions. Instead of locating her face, Snapchat’s detection algorithm reads her breast instead (wearing a cat, lifting weights, adorned in a burning flower crown). In conversation with the classical nude, Darke makes fun with this loophole, in control. She wryly plays with the software’s blunders.

same/different

≠

I/O

[1] Jolene Rickard, “Tomorrow People: Skawennati,” ed. Hannah Claus (Montreal: Oboro, 2017): 1.