This follows a series of short artist talks and Q+As by Vector Festival artists Judith Doyle, Chris Kerich, Amanda Low, and Tobias Williams at InterAccess (950 Dupont St.). This writing draws lines of rot and rhizomes between Low and Doyle’s works. Kerich’s work on death in video games is relevant here, future writing could further consider those connections.

if you are uncertain, you may be wondering

what does it look like?

if the site is drooping and your links are turning purple for unknown reasons, you will want to check

carefully click on all of them

unhealthy ones lead to a 404.

whether the problem is prolonged neglect or a singular changing context

does not matter

YOU MUST ACT QUICKLY!

treating rot as soon as you can will give your site the best chance to survive and be relevant

remove or replace affected links BUT! do not change its appearance as this may cause stress

hopefully now the site can recover

and you will get your beautiful website back

Amanda Low’s http://www.eternallymoving.com/ (2017) is a non-linear poem engaging the concept of ‘link rot.’ When the site a link is pointing to is removed or expires, the link is dead and the server generates a “404 Not Found” page, indicating it could not find the requested page. This is the half-life of the internet: its rotting synapses. Speaking of her work, Low noted the particular prevalence of this issue in the legal community—In 2014, a Harvard Law School study found that 50% of the URLS in U.S. Supreme Court opinions no longer link to their intended references.[1] Low’s poem builds on the already evocative term from the coy (“where am i? i have moved”) to something more fleshy and infected (“i am plagued by something insidious / my ends are rotting”). By giving the internet and perhaps also the illusive links themselves an identity in the form of the first-person, Low articulates a being, one dying a hypertextual death. Though perhaps it is not dying, only shifting: “internally i am always stirring and stirring.”

(A small tangent about rotting ends: there are many metaphors we use to try and understand the internet. The carefree sun-bleached hang ten of net-surfing in the nineties, a series of tubes implies blockages in the pipe, misinterpreting the way things like server capacity function. The information superhighway is another infrastructural metaphor: in some ways very much a utility, to be publicly or privately policed and regulated as such. The metaphor of a cloud leads us to imagine our information, intangible to us on a solid storage device, being held aloft to be pulled from the air. In actuality our cloud information is stored in data banks, in vast warehouses, in the Californian desert: cooled by enormous amounts of ever-scarcer water.[2] In these re-conceptualized internets, I see that a metaphor is not just a poetic turn or a curious connection. It guides perceptions of what something can do and how we interact with it, even future policy actions we take on it. How does the rotting plant-like self that Low suggests in http://www.eternallymoving.com/ guide our perception of the internet? I feel more carefully, more tenderly.)

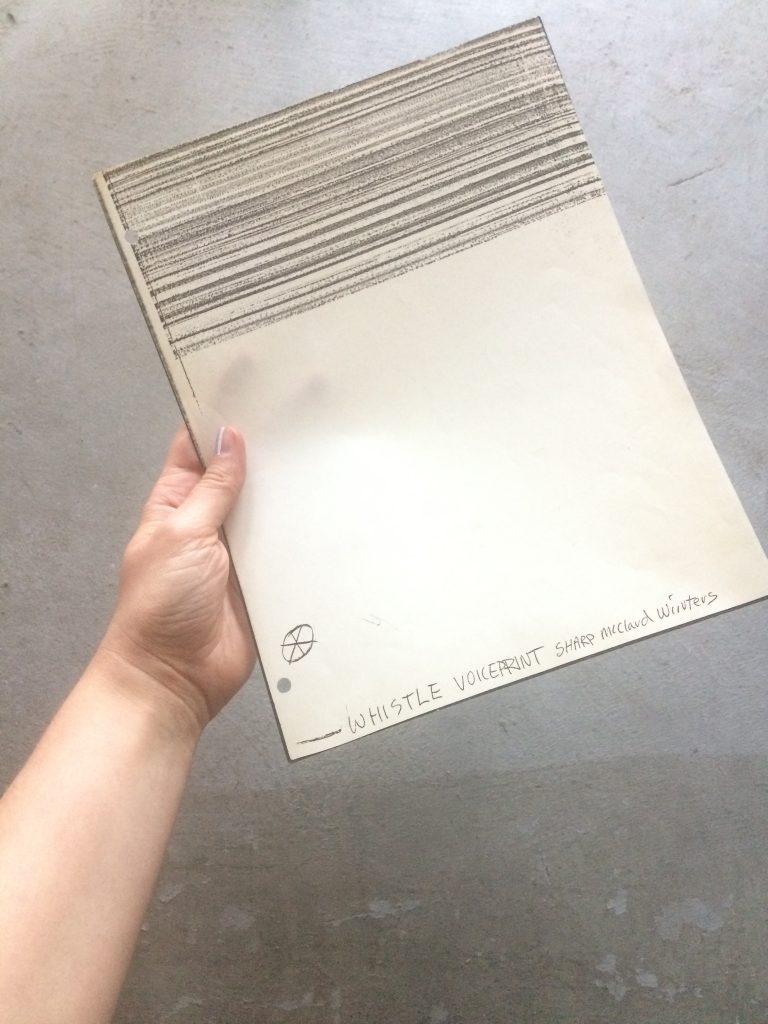

Judith Doyle spoke after Low yesterday, about the collective fax-transmitted work she and her colleagues created in the 70s with Facsimile and WORLDPOOL, responding about rot in relation to artist archives, which haven’t rotted yet. These collectives creatively engaged the first telephonic transmissions as art practice. Creative writing students, they transposed the avatar-like identities and networked exchanges of print publications into fax exchanges. With free faxes enabled by a government code leaked by the Canada Council for the Arts (an excellent example of what agencies and institutions can leverage with the power and access granted to them), the young artists set up connections with artists in other parts of Canada, New York, or Japan. These would be regular party to party networks, with snacks and drinks and company filling the sometimes hours of download time. Like Low, Doyle facsimiles a bodily connection to telecommunications. She talked about the erotic charge of anonymity in sharing publicly, relating conversations about the affordances for porn, between them, as them. Despite the long delay: an electric touch across distance. One of the archival faxes she shows is a voiceprint of artists Willoughby Sharp and Robin Winters whistling into their modem in New York. It looks like static: the trace of utterance. Though Winters is still alive, Sharp died in 2008, some 30 years after the recording. And yet: his breath remains in Toronto in this paper archive. Doyle insists that the rhizomatic network exists in the basements and boxes of artists archives: things rot in order to grow.

Thinking about art spaces and media archaeology, Thomas Elsaesser wonders: “In the face of an electronic present that exceeds us at every turn and eludes our grasp, media archaeology in art spaces becomes symptomatic of the material fetishes we require, in order to reassure ourselves of our material existence or rather: in the mirror of these media machines’ sculptural objecthood we can mourn and celebrate our own ephemerality and obsolescence.”[3] Neither internet nor fax archive is treated as a sculptural object. Low and Doyle might counter Elsaesser from two different angles: Low seeing rot and eternal movement, and Doyle reading not obsolescence in the archive but rather teeming life. Connections rotting and shifting, or lingering even after death.

pppffffffffffffffffsssssssssfffffffffffffffssssssssshsssssssssssssssssssssweeesweeeesweesssssssssssfffffffffffffffsssshhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhssssssshshhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxpssssssspsssssssspssssssssspssssssspssssssspsssssssvrroooooooooommmmmmwwwssppppsssssssssssffffffffffffffffxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxliplipliplipssssssssssssssssfffffffffffffffffffffffffffrrffffffffffffffffgffffffffffffffffffffffffdsssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssneuwneuwneuwsssssssssssssssssfffffffffffffffffffksssssssshhhhhhhhsssssssssshhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxssssssssxxxxxxxxxxxbiannnnbiannsssssssssssssssssssssssssssssppssssshhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhssssssssxxxxxxxxxxxxfffffffffffffffffffxxxxxxxxxxxxyxxxxxxxixxsssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssxxxxxxxxxfffffffffffffffffffvfffffffffffffffffffffffffffwwweeoooooooooooooooowweeeoooooooooooooooowwwwweowwwwwwwssssssssssssssssssssssssssxxxxfffffffffffffxxxxxxxfffffffffffffffffsssfsssfsfsfsssssfsfsfsffsfsfsfsfsfsfssssxsxxsxsfsfsxfsfsxsxsffssxfsfsfxsfsxsxsxsxsssssssshhhhhhhhhsssssssssshhhhhhhhhhhhsssssssssshhhhhhhhhs

[1] Jonathan Zittrain, Kendra Albert, and Lawrence Lessig, “Perma: Scoping and Addressing the Problem of Link and Reference Rot in Legal Citations,” in Legal Information Management 14, no. 2 (2014): 88–99. doi:10.1017/S1472669614000255.

[2] Mél Hogan, “Data Flows and Water Woes,” in Big Data and Society July-December (2015): 1-2. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2053951715592429.

[3] Thomas Elsaesser, “Media archaeology as symptom,” in New Review of Film and Television Studies, 14 no. 2 (2016): 206. doi: 10.1080/17400309.2016.1146858