These are some thoughts arising after Words Before All Else: Oral Histories in the Digital Age, with works by Zacharias Kunuk, Mary Kunuk, Zack Khalil and Adam Shingwak Khalil, Trevino L. Brings Plenty, Elizabeth LaPensée, Skawennati, and Doug Smarch Jr., curated by Jenny Western and Clint Enns at the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Jackman Hall.

“Words before all else: we bring our minds together as one, as we give thanks for the people, now our minds are one.”

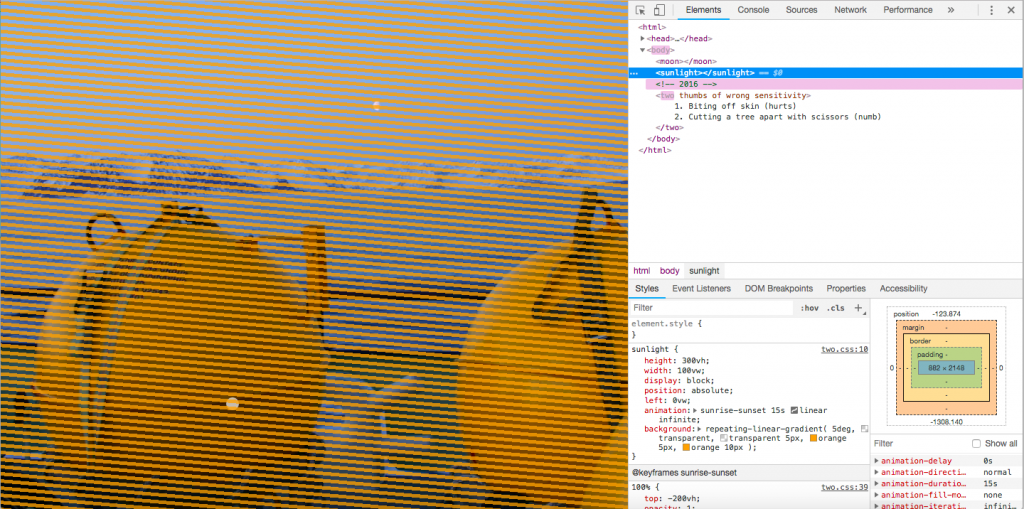

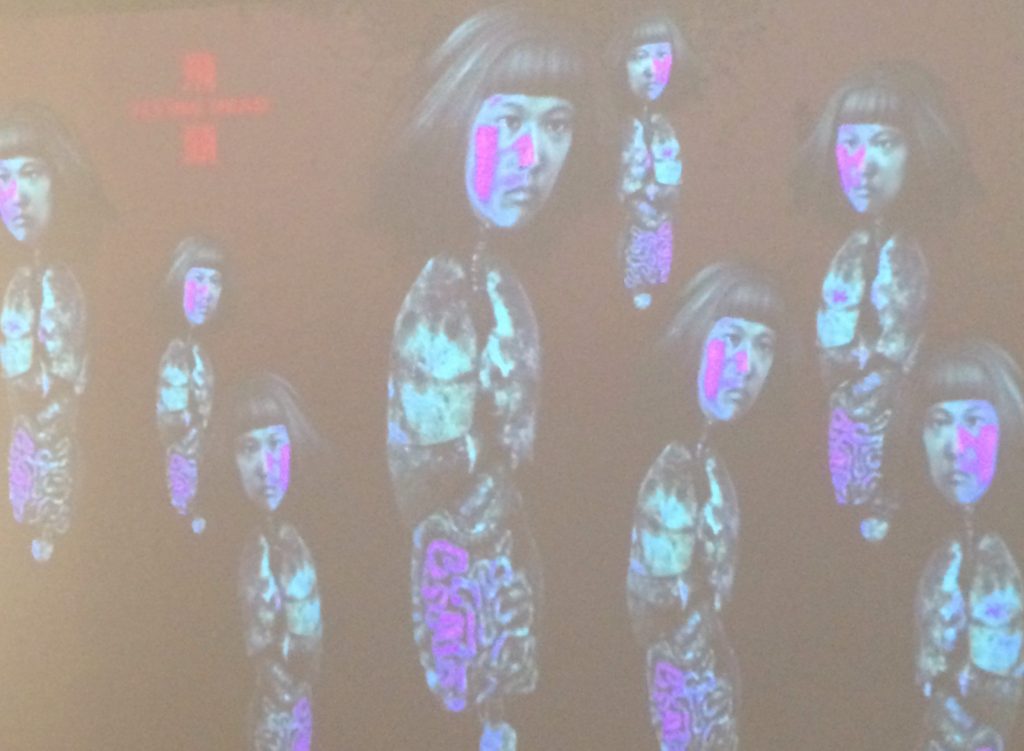

The screening begins with Skawennati’s machinima Words Before All Else Part 1 (2017), which sees her avatar xox recite the above words, the first verse of the Ohen:ton Karihwatehkwen – Haudenosaunee “Thanksgiving Address,” in English, French, and Kanein’kéha, traditionally spoken at the opening and closing of all Haudenosaunee gatherings. The piece is a more recent version along similar lines of her 2002 collaboration with Jason Lewis, Thanksgiving Address: Greetings to the Technological World. Where the traditional address extends greetings and thanks to the natural world—earth, water, thunder, and the many plant and animal beings—Skawennati and Lewis thank the creator for more technological gifts. They extend greetings and thanks to computers, TCP/IP, internet, C++ and Java, and more, bringing our minds together as one.

To bring our minds together: a reminder. Joining each other through spoken words, thanking the natural world as a way of remembering to live intentionally and carefully with it. Through the ceremony of opening and closing, drawn together into a mindset.

Mary Kunuk’s Unikausiq (Stories) engages the oral transmission of knowledge as an act of remembering. “These stories and songs remind me of my childhood and the stories that my mother used to tell me,” she says. “Recording them on video is my way of keeping them alive.” The stories, carefully rendered through hand-drawn computer animation are unexpected and wonderful. In one of them, a snow bunting teases an Inuk arriving on a small island, asking after snow buntings, “you come from nowhere, I won’t tell you where I am. A bird must have shit between your teeth.” The electronic continuation of storytelling into video is something Kunuk’s brother Zacharias Kunuk has spoken about, that “filming traditional knowledge is a way of collecting these old stories and retaining them for the future.”[1] Knowledge is passed from elders by way of the video apparatus. It can be played, replayed, shared widely (through things like IsumaTV’s mediaplayer network and Digital Indigenous Democracy projects).

To pass on, to keep alive. The care of rendering: hand on mouse sketches, clicks, fills in. Traces tears on grandmother’s cheeks, and the ptarmigan she turns into out of grief for her lost granddaughter. What of the relational intimacy of telling?

Zack Khalil and Adam Shingwak Khalil’s The Violence of a Civilization Without Secrets speaks to the valuation of oral history within conflicting knowledge systems. Through archival footage, red-on-white and white-on-red text, and elegant cuts of intersecting horizontal and vertical lines, they tell a story about the remains of a prehistoric Paleoamerican man found in Kennewick. Contrasting the persistent oral histories of the people indigenous to the Columbia River region where he was found that this “Ancient One” was their ancestor, scientists appealed the right to study the skeleton until DNA confirmation eventually confirmed the oral histories. The film also investigates archaeologist’s early interpretation of the skull as having Caucasian traits, and the overwhelming hungry vehemence of white supremacists to use this “science” to “prove” long-standing European presence in the area. “We are not evil, conquering Europeans,” a racist speaker orates, “We will not be swept from this place.” This grasping at shaky soon-disproven hypotheses in lieu of a long lineage of oral history, one of many insidious settler narratives or moves-to-innocence that are further explored in Tuck and Yang’s “Decolonization is not a metaphor.”[2] Shown through media archives, it also holds those of us who are settlers accountable to our acts, our words.

We open and close with more or less intention. To repeat and keep repeating? I keep telling myself. I am still holding on to a story that helped me make sense is no longer true and maybe never was. In the middle of a long conversation I have to take a break and they hold their thought by repeating it to themselves in one long whisper thisthingthisthingthisthingthisthing until I rush back and they can say it to me: this thing. My oma described to me the place she was born. Green layers of mountains and a valley below winding roads and grain-ripe. The sudden rush thunder as she tickled salmon in the stream. She is gone, we go there. I have seen it though not with my eyes before now. None of this is an oral history. We haven’t spoken like that for far too long.

It is impossible to think about words before all else without thinking of the art community’s own recitations: the territorial acknowledgements we give now. What does it mean to do this kind of opening, for the art world? How do we say it? Chelsea Vowel’s excellent article “Beyond territorial acknowledgements” is a reminder that in order to be sites of potential disruption, they must discomfit those who speak them and those who speak and hear them.[3] We need to learn how to pronounce the names—Anishinaabe or Haudenosaunee—of those who made the first treaties in this area, the thinkers who conceptualized the Dish With One Spoon which we all eat from and have a responsibility to renew.

Words can only follow meaningful intention. Settlers have a long history of using words as an apparatus for violence and control. Historically this has manifested in the legal documents of misleading treaties and cultural genocide through language. In the present, words replace action as a form of superficial healing or appeasement. Beyond land acknowledgements, we are tearfully very sorry, we insist that the government’s nation-to-nation relationship is the most important. We’re sorry, we said we’re sorry, we said it. Without clear and articulated intention or action, how can settlers hope to take on the provocation of words?

At a symposium this March at McMaster University on policy and Indigenous Governance, Anishnaabe doctoral scholar Josh Manitowabi spoke about including oral histories and stories in teaching. In thinking about bringing Indigenous knowledge into the education system, he spoke about the difference between sacred stories and teaching stories. Sacred stories need to be told the same way; teaching stories can be changed a bit at the end in order to be specific to a certain lesson or context. What Manitowabi and the program seek to teach, then, is that words matter. They carry meaning: words gain power in material contexts, the places where they’re spoken and heard. How did the context—the physical container of the venue, and the psychological container of the opening and closing—make space for the meaning of these teachings, for their power?

We open and close in context.

Thinking about oral histories and the uttering of words, I think of Maggie Nelson’s reading of Roland Barthes—that the subject who utters the phrase “I love you” is like “the Argonaut renewing his ship during the voyage without changing its name.” In this vein, Nelson says, “whenever the lover utters the phrase “I love you,” its meaning must be renewed by each use.”[4] Our openings and closings and the words we speak should similarly be renewed by each use. Not as rote: rather, imbued with intention.

We can implicate ourselves and our actions and our organizations in them, pushing to disrupt those that speak and hear, accepting responsibility and renewing meaning.

Not tray tables securely stowed not life vests under a seat not silencing cell phones not shuffling papers not final murmur to your companion not a word from our sponsor.

No:

A voice making intentional space.

[1] Kerstin Knopf, Decolonizing the Lens of Power: Indigenous Films in North America (New York: Rodopi, 2008), 340.

[2] Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1-40.

[3] Chelsea Vowel, “Beyond Territorial Acknowledgements,” âpihtawkosisân 23 September 2016, http://apihtawikosisan.com/2016/09/beyond-territorial-acknowledgments/.

[4] Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts (Minneapolis: Greywolf, 2015), 5.